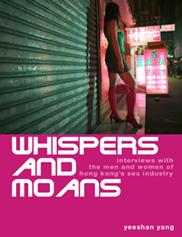

A review of

Whispers and Moans

By

Yeeshang Yang

Published by Blacksmith Books

Yang doesn’t buy any of it. Literally – she refused to pay the hookers she interviewed, knowing that they would only embellish their tragic stories just as they fake orgasms to please the customer. Even when they tell the truth, she remains skeptical about their constant insistence that they are powerless victims. Nor does she have much time for the hookers’ self-appointed guardians whose NGO claims to fight for prostitutes’ rights, or for legislator ‘Longhair’ Leung Kwok-hung’s Marxist angle on the issue. Not that this puts her at odds with the prostitutes themselves, who cannot understand what use activists can be if they won’t make loans.

Most of the action takes place in a strip of Kowloon stretching from the pricy nightclubs of Tsimshatsui East through the karaoke bars up to the streets of Mongkok and Shamshuipo. The market apparently once had some sort of decorum, with clients making a pretence of wooing the courtesans, but that declined with the introduction of huge Japanese-style nightclubs – major businesses churning out hostesses on an industrial scale. Those establishments in turn never fully recovered from the Asian financial crisis. Meanwhile, globalization came along in the form of Mainland whores, who not only drove down prices but offered customers a better-looking and less sullen product. The Hong Kong girls’ resentment echoes that of many of their fellow citizens in other lines of work: lost, helpless and self-pitying in Tung Chee-hwa’s post-boom economy. Nowadays, commercial sex is like fast food: customers pick from standardized lists of sexual acts, and they want it now and cheap.

It is impossible to read these profiles without concluding that prostitutes are largely victims of their own lack of common sense. They commonly enter the profession as teenagers to feed an obsession with owning tacky status symbols they can’t afford and don’t need. Alternatively, they feel driven into it by the need to pay off gambling debts run up by an obviously worthless boyfriend. In both love and money, their decision-making is disastrous. The girls aren’t an emotional mess because they ended up as prostitutes – it’s the other way round. As Yang notes, they are neurotic about keeping lovers, however abusive or dangerous.

For most, the career path is a downward spiral. Club hostesses picking up tens of thousands in tips a night lose it all to a cheating lover or to gambling. They descend into debt and drugs. They age. They spend time in prison or seedy Mongkok brothels. They end up just walking the streets trying to raise enough cash for their next fix. The money follows a similar path. The hostesses “take their revenge on men” by hiring gigolos to treat like dirt; the gigolos do the same with street girls on the cheap side of Nathan Road; the street girls turn for solace to heroin. The heroin, presumably, is supplied by rings headed up by the high rollers dropping huge sums back in the nightclubs.

Yang doesn’t introduce us to many customers. The stereotype is a sad bastard who can’t handle women and who feels he is doing something noble by falling for the hookers’ tales of woe and giving them money. The ones we see in Whispers and Moans don’t contradict this image. Nor do we see much of the ‘happy hooker’, who has her act together and uses the independence and the relatively high income of the job wisely. Off duty, they have homes, kids and respectable lives, and they don’t do interviews.

As Yang notes, not all whores are even considered hookers. The ones who live in apartments in Shenzhen and juggle a small stable of Hong Kong married clients are called concubines. The ones who work their way up the film industry are called stars. The ones photographed by paparazzi escorting ageing billionaire tycoons are called lucky.

For those that sell their minds or souls – the ones called upstanding members of the workforce – this is a book that will amuse and possibly amaze rather than arouse, provided they join the author in having a sense of humour, a thick skin and no sociological or feminist axe to grind.