The Intriguing Life Story

of a Nobody

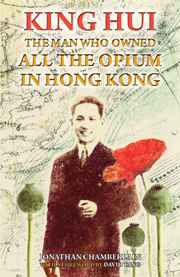

A review of

King Hui – the Man Who Owned

All the Opium in Hong Kong

by Jonathan Chamberlain

Blacksmith Books

Before dying, Hui told this book’s author – a long-time resident active in the community – what he claimed to be his life story. Out of what must be scores of hours of taped conversation comes a unique oral social history, mainly covering the 1930s-50s. Written in the first person, it is a rich account of Hong Kong (and at times Guangzhou) as seen at street-level: family life, food, schools, shops, and corruption, vice and squalor, set against a backdrop of colonial rule, Japanese invasion and communist revolution. The details are often fascinating; for example, details about how some Hongkongers prospered under Japanese occupation. For anyone who wonders what Hong Kong must have been like in those days – the sort of people who look in amazement at Hedda Morrison’s barely recognisable low-rise, third-world town – this is the main reason to read this book.

Hui’s personal story is, on the face of it, intriguing. Trained in martial arts, he was a top student, a hustler, a fighter, a racehorse owner, a womaniser, a possible candidate for marriage to Winnie Ho, a spy, a gambler, a teacher of English to Japanese officers expecting to invade New Zealand, a witness to Japanese torture, a Canton tombola house operator and, as the title says, owner for a brief time of all Hong Kong’s opium. Though at times rambling and discursive (the book is probably best read in small doses), the voice of a real character comes through loud and clear: he did not lead a wholesome or honourable life, and he is defensive, proud, maybe a bit vain.

Was he a liar? The details suggest many of his yarns are true – no-one would make up a story about fighting with a bus conductor while on an essential errand for a wife who has just given birth. The ‘spying’ on the Mainland has an air of authentic banality about it. But sceptics will occasionally hear the voice of a fantasist and find holes to poke in Hui’s tales. For example, the extreme lavishness of his wedding doesn’t tally with his lousy job at the time as a cocktail lounge cashier clerk.

The author says he believes it all; readers will have to make up their own minds. It doesn’t really matter. It is a parable of the unknown Hong Kong Everyman, going from rags to riches and back again but never giving up.