If it’s Tues, 30 May 2006, this must be Shantou – historic city of contrasts, as evidenced by the breathtaking view from my hotel room. After the standard breakfast buffet of congee, baked beans, iceberg lettuce and cha siu bao, my team of intrepid explorers board the minibus and set off into the unknown. “Chiuchow people make lots of money but they are very mean,” Boris informs us. “When a couple get married, people just give them two oranges. Also, they never throw orange peel away – they use it to make candy. The men are famous for beating their wives.”

The first stop is another tea plantation, complete with another quick lesson on the noble art of making what I have long assumed to be an extremely tedious drink. I now know that it is necessary to throw the first dash of hot water out of the pot to clean the leaves – the discarded liquid is known as ‘foot-wash water’. The real purpose of our visit, however, is to try the farm’s honey and, in particular, a bitter, black jelly made from magic bee excrement, which is, inevitably, good for health. So expensive is this precious substance that we are asked to contribute RMB10 towards the free sample.

Thus immune to fatigue, lack of virility, TB and other ailments, we proceed to Chaozhou to examine the old city, with its ancient walls and temple. “Stick together,” Boris warns us, “there are lots of beggars and they are dangerous.” I discover this the hard way on the steps of the Kaiyuan Temple (Tang Dynasty, destroyed during Cultural Revolution, rebuilt with funds from Li Ka-shing et al). A blind woman (late Qing if she’s a day) on crutches lashes out at me viciously with a plastic bowl. Ignoring Boris’s advice to curl up on the ground and pretend to be dead, I flee, slowing her down by zigzagging (they can only run in a straight line). It was a close thing. I would have gone down fighting.

Being off-limits to visitors, the monks’ quarters demand a quick peek through the courtyard doorway. Their saffron robes hang from their verandas. The asceticism of their lifestyle can be judged by the cheap, non-brand name air-conditioning units in the bedroom windows.

After a suitably frugal vegetarian lunch, at which everyone complains about the gritty rice and less-than-fresh stewed celery, we are on the road again, driving through a variety of light industrial suburbs. One district is devoted to manufacturing toilets and sinks, and even sports a Ceramics Capital Middle School. This gives way to the beads zone, which feeds the world’s inexplicable appetite for lurid, sequin-covered handbags. Then we enter the neighbourhood of food additives, which gives way to muddy fields and dilapidated villages. After 20 minutes, we turn off onto a rutted road leading past banana trees, filthy motorbike repair shops, nasty small concrete houses and occasional larger, luxury villas. People sit around doing nothing – it’s as if we’ve suddenly left China and entered Southeast Asia. The only movement is from chickens and dogs, and a few people’s heads turning to watch us. The arrival of a tourist bus is clearly a bit of a novelty. My fellow passengers are oblivious to all this, chatting about souvenirs and previous package tours.

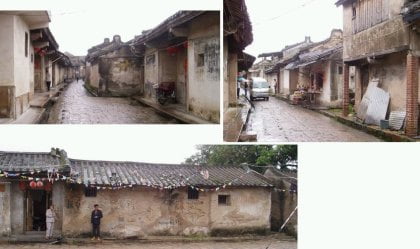

Eventually, we get to Dragon Lake Village. It is an old walled settlement. Boris says it is so poor it qualifies for aid under the latest Five-Year Plan’s rural poverty reduction programme. An expensive board outside welcomes tourists. A few modern, shiny bilingual signs add a dash of incongruous colour to the streets, pointing out supposedly noteworthy features. Otherwise, apart from decently maintained paving stones by local standards, it is untouched. Sewers run down the middle of some streets, under metal grilling. Plants grow through cracked roof tiles. Reasonably clean but shabbily dressed folk tend little shops, waving flies away from orange-coloured chunks of drying tofu or sitting silently in unlit hovels behind a few jars of pickled plums. Through windows and doorways, we spy women of all ages doing piece work – threading sequins, packing little items into plastic bags and gluing gold edging onto paper offerings for the dead. They stare back. Behind a barred window, in a room lined with shelves of dusty boxes, an apothecary in a white coat grinds something in a mortar and pestle.

Children peer out from alleyways and point at the strangers. For the first time, my companions stop prattling. Even after they get used to the smell, they are stumped. The place is waiting to be turned into a theme park, but the government people who put the signs up never came back. There is nothing for tourists to buy. Nothing to pose before for the camera, grinning and making a ‘V’ sign. We are bouncing along in the bus, halfway back to the food additives zone before normal chatter is resumed. “They took us there because it’s free,” Fat Karen tells me.